In the jungle of Indian writers you may have never heard the name of Lalithambika Antherjanam (1905-1985), in spite of the fact that she was a highly regarded writer in her native Kerala. This is perhaps because she used to write in Malayalam, the local Dravidian language, and as far as I know this is her only book translated into English, or at least the only one that is easy to find. It collects some of her short stories and some interesting memoir pieces.

|

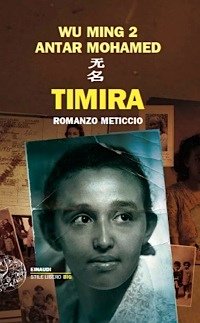

| An antherjan in a recent movie adaptation of Lalithambika's novel "Agnisakshi". |

Lalithambika Antherjanam was born into the Namboodiri brahmin caste in what was then the state of Travancore. She came from a particularly constrictive society: women from her community were kept in seclusion inside the women's quarters of the house, called antahpuram, where they had to go with the upper parts of their body naked. In the rare occasions when they left the house, they had to screen their faces with palm-leaf umbrellas and cover themselves entirely with a piece of unbleached cloth. Antherjanams, the way namboodiri women are called, had to follow strict rules for everything: they could not receive an education and they could only marry the eldest son of a namboodiri household. For the slightest transgression of the rules, antherjanams were trialed and cast out of society.

Lalithambika had the luck to have an illuminated father, who gave her an education. However, when she threw away her palm-leaf umbrella and went to a meeting of feminist activists she was cast out, together with her husband. She began her career as a writer, in spite of the disapproval of everyone. Her stories are all about women: women who committed sins and ended their life in poverty or repentance, young widows whose lives have been shattered by the untimely death of their husbands, mothers who have lost their sons in a war or for the strict rules of their community, and even a prostitute and a yogini. Whether social workers like Bhanumati Amma in "Come back", or strong mothers in the isolation of a farway city like Meena Mami in "The Boon", or again disillusioned wives turned prostitues in what is in my opnion one of the best pieces of the book, "The Goddess of Revenge", the women in Lalithambika Antherjanam's book are hard to forget. If you like Mahasweta Devi's stories about women and tribal people, about injustices and unspeakable horrors, then you would probably like Lalithanbika's work. She was inspired by the work of Tagore, especially by his novel "The Home and the World". As a result, her stories are impregnated with activism, to the point that some of them are more an exposure of some unbearable wrongs in the namboodiri society than a pleasure to read for the way they are written. However, I am only reading this in translation, and I might never know how the stories were like in the original form. The book is interesting also from an anthropological point of view, to understand the customs of this small community, resistant to the changes that nationalism was bringing throughout the country.

"Cast me out if you will. Stories and Memoir" by Lalithambika Antherjanam

Translated and edited by Krishnankutty, with a foreword by Meena Alexander

Published by The Feminist Press at CUNY, 1997, pp.188